Today, June 30, is Ellen Maurer's fiftieth birthday. A year ago I posted my article "On losing a sister to murder"—I don't want to repeat those sentiments now, I just want to remind the world that she really did exist.

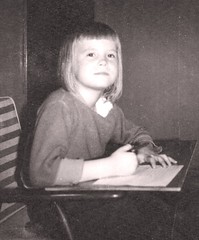

Today, June 30, is Ellen Maurer's fiftieth birthday. A year ago I posted my article "On losing a sister to murder"—I don't want to repeat those sentiments now, I just want to remind the world that she really did exist.The first photograph, at left, was taken when I was six years old and she was not quite four. We were standing on Elmwood Avenue, near the (then) local Boy Scouts offices in Evanston, Illinois. A half block to our north was Dempster Street, an important east-west artery, and the street we walked up to go to our elementary school. A half block to our south was the informal and slowly shifting boundary between our predominantly white neighborhood and the nearest predominantly black neighborhood in the Evanston of my childhood. A little further in that direction was Nichols Junior High School, where our troubles began.

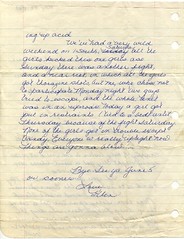

The second photograph shows her writing to our grandparents in Europe. I have a photo from the same date in 1962 showing me doing the same thing. The picture reminds me of the fact that when she became a teenager she was constantly writing. Her letters from Ridgeway Hospital and the Illinois State Psychiatric Institute are among my most precious possessions, but she didn't just write letters. She was bitten by the Motown bug and constantly wrote song lyrics that, in her mind, would be just perfect for Smokey Robinson and the Miracles or the Temptations. She wrote a novel, which, after her death, my parents kept in the bedroom that they maintained as a shrine to her, but I was not allowed to read it. Now I have no idea what happened to it. Her intelligence was no secret to her teachers, who had already promoted her directly from first to third grade.

The second photograph shows her writing to our grandparents in Europe. I have a photo from the same date in 1962 showing me doing the same thing. The picture reminds me of the fact that when she became a teenager she was constantly writing. Her letters from Ridgeway Hospital and the Illinois State Psychiatric Institute are among my most precious possessions, but she didn't just write letters. She was bitten by the Motown bug and constantly wrote song lyrics that, in her mind, would be just perfect for Smokey Robinson and the Miracles or the Temptations. She wrote a novel, which, after her death, my parents kept in the bedroom that they maintained as a shrine to her, but I was not allowed to read it. Now I have no idea what happened to it. Her intelligence was no secret to her teachers, who had already promoted her directly from first to third grade.The third photo: Here she is in April 1969, about three months before her fourteenth, and last, birthday. I took this photo using my father's Polaroid camera, which I wasn't sure how to use—hence the streaks. By the time I took this picture, she had already run away from home a number of times, starting the year before, which happened to have been the first year I began keeping the diary that I still maintain. The chronology is all there.

The terrible alienation that drove Ellen from our home over and over again began when she made a new friend at Nichols. That girl was black. Somehow I had subconsciously known to keep my interracial school friendships out of my mother's field of vision, but that kind of caution would not have been my sister's way! But in any case, how could she have anticipated such a devastating response from her mother? The warmth instantly drained out of their mother-daughter relationship, my father did nothing to intervene, and Ellen and I became conspirators for sanity in our own home.

Our family poison, racism, may have sprung at least in part from my mother's own growing-up years in a Nazi-dominated, tight-knit German community in Japan. After this rupture in our family, Ellen took an interest in black culture and music, and increasingly rejected the white middle class. When she ran away the first time, she was found by the police in a car with a black man who was (we were told) wanted on an illegal firearms possession charge. Most of her disappearances were to black neighborhoods and households in Evanston and then Chicago.

The consequences got worse with each escapade; first, just warnings; then, a private psychiatric hospital; then, a foster family in Ann Arbor, Michigan; then Chicago's juvenile jail, the Audy Home. Her letters (there's a great example at left, from May 1969) described what life was like in those places. Finally, as nobody seemed to have any better ideas (certainly not investigating the hermetically-sealed household she came from), she was placed at the Illinois State Psychiatric Institute. And that is where I visited her for our last times together, and where we both had wonderful conversations with a very engaged and understanding clinical staff.

The consequences got worse with each escapade; first, just warnings; then, a private psychiatric hospital; then, a foster family in Ann Arbor, Michigan; then Chicago's juvenile jail, the Audy Home. Her letters (there's a great example at left, from May 1969) described what life was like in those places. Finally, as nobody seemed to have any better ideas (certainly not investigating the hermetically-sealed household she came from), she was placed at the Illinois State Psychiatric Institute. And that is where I visited her for our last times together, and where we both had wonderful conversations with a very engaged and understanding clinical staff.In mid-March 1970, she disappeared from ISPI. I got a call from her on my birthday, March 23, but she didn't reveal her location. On the 28th, my father was summoned to the Cook County morgue.

Related:

Ellen Maurer remembered

I have just read an amazing and inspiring book, one that I should certainly have read many years ago and somehow missed: Eugenia Ginzburg's Within the Whirlwind. It represents the second volume of her memoirs—the first having taken readers through her arrest and seven-minute trial and her subsequent entrance into the world of the Soviet Union's arctic GULags. But it is not just a book. It is a very special legacy for every human being, a true monument to humanity, to all the human heart can endure and do and be under circumstances of systematic, institutionalized cruelty.

I knew that the book existed; it is part of the genre of concentration camp literature that anyone who has studied the Soviet Union has been exposed to. This particular copy somehow made its way into my hands one day while I was whiling away the time in the library of Portland Mennonite Church. The timing must have been right; the book struck me in a deep place. I even began to have a sense of reverence for the physical book, the pages with her words on them, because they were words of a person who loved and even married in those Siberian conditions of calculated cruelty, who recorded the unspeakable with kindness, humor, irony, intelligence, and honesty, and who saved lives. And even with those hundreds of lives this self-trained nurse touched but could not save, she often provided a moment of kind companionship as they breathed their last.

Russians are capable of endless discussions on the romance and value of the intelligentsia, as well as their alleged uselessness and vanity. Wherever the truth ultimately lies about the intelligentsia and their cultural and class realities, I'm profoundly grateful that Soviet society still had the capacity, however weak it became, to nurture a literate and loving conscience. Eugenia Ginzburg is exhibit A.

I have just read an amazing and inspiring book, one that I should certainly have read many years ago and somehow missed: Eugenia Ginzburg's Within the Whirlwind. It represents the second volume of her memoirs—the first having taken readers through her arrest and seven-minute trial and her subsequent entrance into the world of the Soviet Union's arctic GULags. But it is not just a book. It is a very special legacy for every human being, a true monument to humanity, to all the human heart can endure and do and be under circumstances of systematic, institutionalized cruelty.

I knew that the book existed; it is part of the genre of concentration camp literature that anyone who has studied the Soviet Union has been exposed to. This particular copy somehow made its way into my hands one day while I was whiling away the time in the library of Portland Mennonite Church. The timing must have been right; the book struck me in a deep place. I even began to have a sense of reverence for the physical book, the pages with her words on them, because they were words of a person who loved and even married in those Siberian conditions of calculated cruelty, who recorded the unspeakable with kindness, humor, irony, intelligence, and honesty, and who saved lives. And even with those hundreds of lives this self-trained nurse touched but could not save, she often provided a moment of kind companionship as they breathed their last.

Russians are capable of endless discussions on the romance and value of the intelligentsia, as well as their alleged uselessness and vanity. Wherever the truth ultimately lies about the intelligentsia and their cultural and class realities, I'm profoundly grateful that Soviet society still had the capacity, however weak it became, to nurture a literate and loving conscience. Eugenia Ginzburg is exhibit A.

3 comments:

interesting blog. this quaker faith you speak of ...what distinguishes it from other christian faiths ? i always get confused about all these things

Dear Pseudo!

I wonder why you claim the title of "pseudo." To me, the pseudo would mean that you want to enjoy the appearance and reputation of an intellectual without doing the work. (What is that work? One definition: engaging in dialogue about ideas.) By leading with a question and an admission of limitation, you may put your pseudo status in question.

Now watch me squirm as I try to give a straight answer to your legitimate question. Quakers in general are nothing more or less than a particular stream of Christian history, spirituality, and discipleship (definition: set of understandings of the behavioral and ethical consequences of a faith, and personal disciplines to keep the faith fresh). Our anchor in history is the Puritan revolution of mid-17th century England.

On the "feeling" level, I'd say Quakers are distinguished, although certainly not made unique, by what seems to me to be a wonderful combination of grace, simplicity, and spiritual alertness. We prefer to gather around Jesus as our teacher instead of depending on formulas, ceremonies, and authoritarian leadership.

At our best, this results in little communities (most Friends meetings and churches are not large) of tender people who practice straight talk, nonviolence, equality of men and women, relatively simple lifestyles, and service. At our worst, we get as fragmented as the larger denominations, have a hard time opening our doors to others who aren't Quakers, and occasionally get too obsessed with our own specialness.

Here are some more formal answers to your question on the Web site of my church. I'm not avoiding personal answers by linking to these pages, because I wrote the text at those pages.

http://www.reedwood.org/AboutFriends.htm

http://www.reedwood.org/General.htm

Johan

Dear beppe!

Thank you for your kind words, and for reading about my sister. Your comments really meant a lot to me.

The crisis with my sister INSIDE my family, and the moral bankruptcy exposed by the Viet Nam war OUTSIDE my family were two factors that broke the hold on me of my family's cult of obedience. After passing through an awful period of total cynicism, I became acquainted with Jesus, and found that trust was still something I could experience.

Post a Comment