|

| Cave Creek, Arizona, 1957. |

I grew up in a one-church, two-bar town, in the first set of mountains north of Phoenix. It was a quirky little town, and it was a mystery to me why all my friends’ dads could fix pickup trucks and build concrete floors, but my dad could only read ancient Greek. He was the pastor in that one church, and for a while had been a denizen of one of those bars.

Then, mercifully for me, he joined AA instead. But I did not understand that then. All I knew is that he no longer smelled sticky and sweet when he picked me up, and his powerful voice no longer used to scare me into diving under the table or behind my older brothers. When he came home, we used to listen for his beautiful whistle. He would whistle Bach cantatas but only when sober. It was a very good sign when we could hear the engine shut off, the door open and close, and -- wait for it -- Bach in the clear desert air. But after a few years I just learned to enjoy the whistle. Unlike many of my grade school classmates, I could rely on the fact that my dad would come home that evening, sober.

Still, though, his head was generally in the needs of his congregation, or the complexities of Greek verbs, and not the physical exigencies of pickup trucks. There was, however, one night in the year when I could be sure that my dad’s abilities were of practical use. Just before Christmas, out where huge boulders had tumbled down the mountainside eons ago, I’d huddle next to my best friend, always in the children’s choir, I‘d see his profile in the candlelight, rocking slightly on his feet. I’d listen for his booming liturgical voice say, “And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God.” It was the town’s Christmas pageant.

As he spoke, one of the older girls would stand on the path just above a huge boulder and stretch out angelic arms. A young woman would be walking underneath, past boulders nestled into the ground. The young woman would feign terror, then awe, while my father’s voice still boomed out the words of Luke’s Gospel. She was always accompanied by the littlest angel, my coveted role. The year I was about the age for it, the women organizing the pageant -- it was always women -- chose a little girl with lovely red curls who had lost her baby sister in one of the valley’s floods. The baby had been born after her father died of cancer. Even I understood why she needed to be the littlest angel instead of me.

|

| Dianne and Judy |

My brother says that the Christmas after I was born, my mother wrapped me in so many blankets she was afraid I couldn’t breathe. “Check the baby! Is she still breathing?” my brother said she repeated all the way through the pageant. It was the last time I was warm at the pageant. All through the pageant, year after year, Dianne and I would stand next to each other, probably for warmth. The setting sun stole all the warmth from the air, as the mid-winter desert night grew cold. It gave me some appreciation for the first-century shepherds out in the fields by night, as well as for my brothers, draped in serapes or whatever blankets were at hand, playing shepherds in the pageant.

At the right time, with my father’s voice, they would cross the area between piles of boulders just large enough for a stage. A huge pile of smaller boulders formed the audience’s bleachers, and the huge ones opposite were the huge boulders that one’s imagination transformed from an angel’s platform to an inn to a manger scene as my father’s voice rang out the Christmas narratives from the Gospels.

The audience, mostly from Phoenix because most of our town had to be in the pageant or helping with it, had been guided in by luminarios -- paper bags half-filled with sand with lit candles embedded in the sand. The luminarios lined the road out of town on both sides, for miles. I thought they were magic.

They were not. When my other brother was in middle school, he and the other kids would ride on the back of a pickup with the sand and the bags and candles. They’d hop off, fill up a few bags, drop them off with candles, and then hop back on the pickup. When the sand got low, a guy named Montana, the town’s heavy equipment operator, was supposed to come out and fill the pickup with sand again. But it was a long day’s work, and as it stretched out, Montana wanted a drink. So he stopped off at the bar. When they reached him at the bar -- everyone would have known which one to call him at -- he was well-settled in and didn't want to leave. No problem -- in our town, most of the ground was sand, with outcroppings of granite. So Montana simply went outside, dug a hole with his backhoe, and loaded up another pickup. Right in the middle of the bar’s parking lot.

In between Christmas pageants, Dianne and I faced the woes and joys of childhood together. Our mothers were best friends; I met her first when I was a babe in arms, and she was in her mother’s womb. I spent many an hour playing under the kitchen table with Dianne as our mothers plotted the next community event or way to fund the next school project -- milk for children’s lunches or playground equipment. School money was sparse in Maricopa County then. Probably still is.

My parents were New Englanders, and I was packed off to boarding school in Massachusetts at 14. As the years went by, I lost touch with Dianne. Then one day, when my children were the age to be in the choir themselves and we were living in Indiana, my brother called me. Dianne’s 13 year old daughter had died in a car crash. I wasn’t able to make it for the funeral, but came home some months later, when the grief and loss had sunk in, terribly. In those months, Dianne had begun transforming her grief into a profound life change. I do not know how one finds the strength to do that; I admired her deeply for it.

|

| Sea of Cortez. Photo by Judy. |

Dianne and the Sea of Cortez

We saw only sea when we sat down. Tiny points of rock

pierced the waves. Water over the sandbar calmed, and the sea

sought its escape in a blue-green strait alongside.

The rocks rose into reefs. A land bridge to the estuary surfaced,

grain by grain. I listened to you as the sea

lost its arrogance, a retreat hidden

in each break of wave on wave.

Sandpipers skipped

along pools of water. A heron

stared at fish in newly-shallowed pools. I listened to you

as the current released its treasures to the sand.

When it was done,

when Venus hung over the new moon and sunset

showed us peaks across the sea, you finished telling me

how your daughter died. And I said,

"I won't be twenty years

coming home again."

|

| Dianne Reichenbach. Photo by Judy. |

But no. Her sister called me one day and said she was in the hospital, with cancer throughout her abdomen. She was 55. “It doesn’t sound good,” her sister said. In the next few years, I came home when I could, in August and January, because that’s when I’d be back from Russia. There is no greater love than visiting someone in August at the far northern reach of the Sonoran Desert.

I called her from the airport. “I’ll be asleep by the time you get here,” she said. “I hope you have a flashlight. The light is out and there are rattlesnakes under the porch.” I’m home, I thought, I’m home! I had known to pack a flashlight. Rattlesnakes love the sundown in the summer as much as humans do. In those circumstances, flashlights come in handy.

|

| Photo by Judy. |

I loved her house. While not in the best repair, its walls had bright bursts of color, turquoise and gold and oranges tumbling into each other, Mexican-style. She made old wooden pallets into a display case in her backyard. She coaxed flowers out of the desert sand and granite. The town had completely changed; from a quirky town it was now a quirky suburb with a wealthy retirement center nearby. But her house, for me, was home.

As she grew weak, she kept more and more to her bed, which had a beautiful view of dawn and a palo verde tree. I noticed on her dresser a framed copy of my poem, and a photo of the two of us at about 5 years old.

When I was leaving the last time, she said as a goodbye, “Vaya con Dios.” She had thought carefully about how to say goodbye. We knew we would not see each other again.

I tell you this now because when I hear “Joy to the World,” I do not think of how the Savior reigns. Instead, a grief wells up from deep inside me. When I hear “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” I do not contemplate the town’s deep and dreamless sleep. I am too busy fighting tears.

My father is gone now as well. Born on Christmas Day after the close of World War I, he died on Good Friday, 2005. While I love Christmas morning, there’s always a bit of emptiness gnawing at me without the birthday cake and candles, his voice, and of course, the whistle. He loved giving the Christmas day service, because only the most faithful showed up. So we would wait, in some agony, until he arrived back home. By the time I was coming home from boarding school or college, he was serving at a large church in Phoenix.

I wouldn't give away for a moment my connection with Dianne, but it does make the holiday season tough. Why pretend otherwise? Jesus of Nazareth did not sugar-coat, which the Pharisees learned to their surprise. Why then should we cover our grief at Christmas with a dusting of candies and sugarplum fairies? Christmas is to celebrate the birth of the Word become flesh, who said, “You shall know the truth and the truth will make you free.” So why do many of us have this idea that it’s wrong to feel our emotional truths, including sorrow and loss, at Christmas time?

Although it’s uncomfortable and perplexing, and infuses your being with a sense of helplessness, grieving is a good and life-affirming thing. When grief calls your name, the only thing left to do is answer.

Paul says to “rejoice with those who rejoice; mourn with those who mourn.” It applies at Christmas time as well. Jesus honored Mary and Martha’s tears. He will honor yours, as well, in whatever season of the year they fall.

|

| Judy (middle) at the Tretyakov Gallery. |

|

| Judy and her dad. |

Her previous guest posts are here:

Sitting in the Russian section.

Accents, eggnog, and foreigners in our midst.

Shari Lane on sadness.

Mike Farley on another kind of hope.

Rosalie Ruetz on climate doomism, its danger, and its silver lining.

Jackson Wu on deconstruction, reconstruction, and arguing in good faith.

Alexandra Petri's Advent.

“The world is very bleak,” Mary went on, “generally inhospitable to refugees and the poor, and everybody is competing for resources that aren’t distributed well.”

“No,” Joseph said, “they aren’t. I don’t get any parental leave at all.”

“I was going to count on my cousin to help out, but she just conceived,” Mary said.

Brian Bantum: SpaceX, Meta, and the Christ Child.

In the midst of this allure of escape, I am reminded again of the sheer wonder of Christmas. In the face of all our many ways of saying no to a life with God, God chooses to say yes to us again.

Colleen Dunne's inside view of Dorothy Day's canonization process.

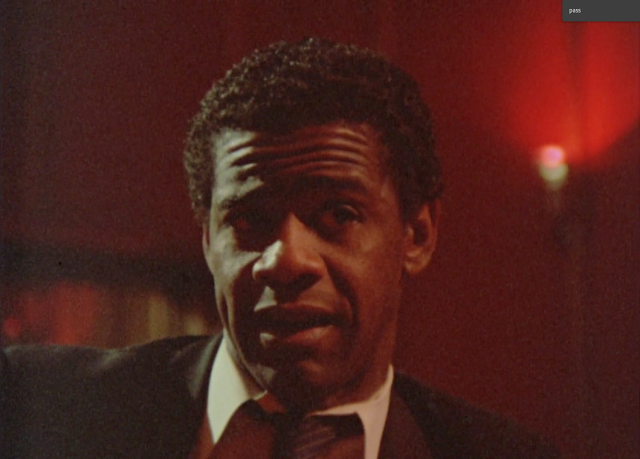

Al Green, "Pass Me Not." (From Robert Mugge's film Gospel According to Al Green.)

This video can't be embedded, so please click on this link to view the video on Vimeo -- and explore other videos in Mugge's fantastic Vimeo catalog.

|

| Screenshot from "Pass Me Not." |

No comments:

Post a Comment