|

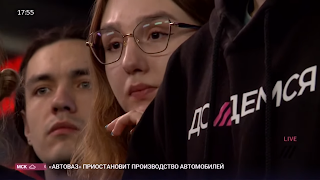

This evening, Moscow time, Natalya Sindeyeva and her team at Russia's "optimistic channel," Dozhd' (Rain) suspended its work and went into hibernation after a final, very emotional goodbye broadcast. I defy anyone to watch this program (in Russian, or through the auto-generated subtitles in your language) without tears.

Among those who spoke at this final broadcast was Vera Krichevskaya, co-founder of Dozhd' with Sindeyeva and director of the new film F@ck This Job (based on the history of Dozhd'). She summed up in three sentences why the channel had to stop: "In the last several days, the Russian Federation adopted new laws. These laws obligate us to tell falsehoods. If we have to choose between telling falsehoods and temporarily turning off our signal, we choose to turn it off...."

I have been a Dozhd' viewer and subscriber practically from its beginning. My current subscription supposedly runs for another 632 days. I've even gotten used to the legally required disclaimer, in big letters, that for the last half-year has described the channel as a "foreign agent."

Among the new laws and regulations are a requirement that all statements about the "special operation" launched in Ukraine last week must come from the Russian military, and that the word "war" must not be used. All words and images that the government designates "fake" are outlawed on threat of fifteen years' imprisonment. This is a dramatic escalation of a process that began with the new century and its new Russian president, gradually squeezing the air out of Russia's independent mass media and causing an impressive stream of Russian journalists and commentators to flee the country, including Dozhd's own editor-in-chief Tikhon Dzyadko just yesterday. Almost every prominent independent voice in Russia's mass media has now been driven off its normal channels, forced to use such platforms as Youtube, Twitter, Telegram, and Instagram, which themselves, to varying degrees, are under threat of suppression.

I remember sitting in our car back in Richmond, Indiana, around 1987, listening to the news, when I heard a startling story: The USSR's KGB had come in for public criticism in the Soviet press. I was genuinely amazed; this was my first concrete evidence that Gorbachev's policy of glasnost' (transparency; openness) was real. When I began my regular visits to Russia a few years later, the difference in journalistic freedom was evident everywhere I looked. (Here's a sample.) That era has emphatically come to an end.

President Putin has claimed that all media worldwide dance to the tune that the pipers (those who finance the media) are playing, so why point the finger at Russia? Of course there is a lot of truth in this, but he was not arguing for a reform of this reality. He was simply deflecting the attention being paid to the fresh waves of repression in Russia. Rather than do a case-by-case comparison of the reality in Russia with the reality elsewhere, I think it is fair to compare today's reality in Russia to the era of glasnost', to 2000, or even to 2014.

Of course there are many informal channels of information that operate in Russia, as everywhere else. Frank face-to-face conversations, especially in kitchens, went on even during Stalin's repressions. We had plenty of those conversations in our own kitchen in Elektrostal! Telephones and the Internet serve ordinary people as before, subject to the constant awareness that someone might be listening or recording us. The government cannot suppress all individual dissent; its main priority is to suppress effective mass dissent. Those who post or repost anti-war or anti-leadership texts and memes within their own social-network circles will usually get away with it; the government will arrest a few to discourage the rest, but most of the repression is reserved for those the authorities believe have wider influence.

UPDATE: It looks like more people are getting police attention for signing petitions, so my optimistic comment that most protesters "will usually get away with it" may now be out of date.

No mass media or Internet channel delivers a perfect stream of pure information -- defined as objective facts or fact-based recommendations that any member of the audience can rely on to make judgments and decisions. For me, there is another form of valid information: finding out what others believe to be facts, and what they believe to be persuasive arguments, along with enough context that I can make my own evaluation of those assertions. I want to hear the Russian government officials' points of view. I want to hear their opponents' points of view, and the evidence of ordinary people who must endure the consequences of all those decisions.

For example, these days I'm following news from Ukraine on a variety of channels on Telegram. Much of what I hear seems unlikely to be the whole picture, and most of it is obviously intended to influence rather than simply inform me. Often the various channels are simply quoting each other rather than each delivering fresh news from their own sources. However, taken cumulatively, I can form a reasonable, if tentative, impression of what's going on -- good enough to help shape my prayers.

There's also another form of information that is extremely valuable to me: what are the relationships and interdependencies among all these actors? Who treats whom with kindness or cruelty? Who keeps their promises, who breaks them, and what are the consequences? I want the evidence of these relationships and interdependencies to be sufficiently visible for me that I can consider how to fulfill my own obligations as a citizen of the world and of the Kingdom of God.

In any case, I believe I can tell the difference between "information" and "instruction." Russia's leaders have chosen the latter. Hence the very sad reality of today's last (for now) studio program from Dozhd'.

Update: Here's the Washington Post's summary of the media situation in Russia.

(Also see this post from July 2022, in which Dozhd' returns to the air—but in exile.)

|

| Source: Ebay. |

When I was growing up, our family had a shortwave radio, a Hallicrafters S-120 receiver, which my sister Ellen and I listened to frequently, trying our best to search out faraway stations with unfamiliar languages and accents. We knew that, during World War II, my father's family had a radio that they used (at great risk of discovery by the German occupiers of Norway) to hear what was going on beyond the Nazi curtain.

I was a shortwave radio user right up until the early 1990's. Toward the end I had a small shortwave receiver that I used to carry around the streets of Richmond, Indiana, and Wilmington, Ohio, listening to the BBC World Service through earphones on my evening walks. That's how I followed the day-to-day drama of the end of the Soviet era and the birth of today's Russia.

For all but the community of shortwave enthusiasts, the Internet has replaced radio as a way to listen to faraway broadcasters. If the Internet ends up, in some places, becoming a gated resource for those who prefer to instruct and control rather than inform, I wonder whether we'll see a rebirth of shortwave.

Do you remember ambassador Marie Yovanovitch? David Remnick interviews her.

Sergei Chapnin on Russian Orthodox Patriarch Kirill and Vladimir Putin's "two wars."

Tomorrow, March 4, is the World Day of Prayer. Many years ago, I participated in planning an ecumenical service for this occasion. I was one of the two Quakers, and the only male, in this group in Ottawa. I was delighted to see an article by British Quaker Stephanie Grant, who wrote for this year's event.

Micah Bales on seeing the face of Christ.

Roger E. Olson on becoming Anabaptist.

Eric Bibb and Michael Jerome Browne, "Needed Time."

I'm down on my bended knees....

No comments:

Post a Comment