Once upon a time, my Friends World Committee colleague and mentor Gordon Browne wrote an article for Quaker Life magazine in which he mentioned the term "liberation theology." The editor wrote back asking Gordon to delete that phrase. Use the concepts, the editor advised, but don't use the label.

With some regret, I understood the editor's reluctance to include the reference, which for much of the Quaker Life audience was code for Marxist heresy, even if Marxism was the last thing on Gordon's mind. A more complete explanation of liberation theology was beyond the scope of his article, so he made the change.

I remember my first introduction to liberation theology, not as a book or movement, but as a fascinating reality. The time: summer 1975, just a year after I became a Christian. The place: Voice of Calvary's campus in Mendenhall, Mississippi, about which I wrote here in this blog back in 2005.

During my time at Voice of Calvary, we talked a lot about two books. The first and by far the most emphasized book was the Bible, which was at the center of our group life. During the summer, Artis Fletcher led us through a close reading of the book of Hebrews, for which I'm grateful to this day. Bible references were laced into most, if not all, of our group discussions seven days a week.

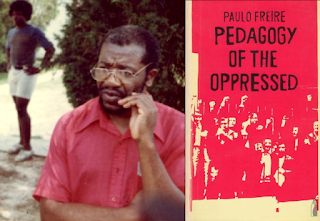

|

| VOC founder John Perkins introduced us to Freire's book. |

While Freire's book is not explicitly Christian—it has become a classic of educational theory and practice—it has dramatic implications for Christian discipleship, spirituality, and evangelism. Above all, it equips and encourages us to identify and confront the forces that dehumanize the people we seek to serve, and to do that work alongside those very people. It models the clarity and humility that marks true dialogue, as in these words from the author's own preface:

This volume will probably arouse negative reactions in a number of readers. Some will regard my position vis-a-vis the problem of human liberation as purely idealistic, or may even consider discussion of ontological vocation, love, dialogue, hope, humility, and sympathy as so much reactionary "blah." Others will not (or will not wish to) accept my denunciation of a state of oppression that gratifies the oppressors. Accordingly, this admittedly tentative work is for radicals. I am certain that Christians and Marxists, though they may disagree with me in part or in whole, will continue reading to the end. But the reader who dogmatically assumes closed, "irrational" positions will reject the dialogue I hope this book will open.

When I look back at both occasions (Voice of Calvary and Quaker Life), I'm struck by one thing in common: I don't think that Voice of Calvary was any more eager to publicize to the general public, and to its donors, that we were encouraged to read Pedagogy of the Oppressed, than Quaker Life was eager to print the phrase "liberation theology."

These thoughts about liberation theology were provoked by an article by Christianity Today editor-in-chief Russell Moore, "Christian Nationalism Cannot Save the World"; and by a response from pastor and scholar Malcolm Foley, "Liberation Theology for White People: The Preferential Option for Moore."

Foley agrees with the main thrust of Moore's argument, which might be summarized by this paragraph from Moore's article:

Christian nationalism is a kind of Great Commission in reverse—in which the nations seek to make disciples of themselves, using Jesus’ authority to baptize their national identity in the name of the blood and of the soil and of the political order.

Malcolm Foley's response was provoked by what may have been a gratuitously glib throw-away line on Moore's part, or it may have been a peek into evangelicalism's persistent inability to understand liberation theology. The line Foley objected to: "Christian nationalism is a liberation theology for white people."

Foley's objections (but please read his essay) ...

First, Moore is saying that it [liberation theology] is a Christian heresy. Second, he is saying that Christian nationalism is "political" in a way that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is not. Third, he is saying that liberation theology is not for white people."

From all of these cases, what should I conclude? Apparently "liberation theology," without regard to the merits of its diverse expressions and its origins in Christian dialogue, is misunderstood and dismissed by people who assume that we don't need to be liberated. At least not "that" way. Maybe "liberation" is for some awkward constituency elsewhere, whom we really don't sense a kinship with. Maybe there's even a lingering suspicion that "liberation" is narrowly political, probably violent and dangerous, and has nothing to do with our own eternal destiny.

Meanwhile, people who think we don't need liberating are looking at a world threatened by rising tides of xenophobic nationalism and authoritarianism, a resurgence of racism that is only aided by white defensiveness, and economic forces that hold us hostage in the face of global warming. What can liberate us to meet all these challenges with the power of a diverse people united in Christ?

At least part of the answer was modeled for me by Voice of Calvary: building a community that expects joyful surprises. Urban and rural people from nearby and all over the continent working across racial lines to benefit each other and the kids around us, asking each other awkward questions and enjoying each other's company. Studying the Bible together line by line, some for the first time, in the specific context of Mississippi ... and (just imagine!) with the help of a pioneering Brazilian educator who taught us not to be afraid of the word "liberation."

Yury Zhigalkin on the foreclosed futures of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Amy Medina was so sure she would never accept another job that required raising her own salary....

Nancy Thomas: are our regrets mosquitoes ... or monsters?

Vinyl and the search for perfect sound. (And can you really spend over $360,000 on a turntable?)

I'm still paying tribute to Albert Collins. Here he's at Montreux: (cued up at "Cold Cold Feeling"; click here for the whole set)

3 comments:

The work of Paulo Freire was foundational for my teaching ministry in Bolivia, which included training Bolivian teachers. Also influential were the writings of activist theologians Rene Padilla and Samuel Escobar who adapted the concepts of liberation theology to the Latin American Protestant setting. They coined the term "mision integral" (holistic mission) and their influence continues today.

Thanks for this blog.

Thank you, Nancy!

To your question of "What can liberate us to meet all these challenges with the power of a diverse people united in Christ?"

A consciousness and conscience in the direct and continuous presence of the spirit of Jesus Christ. Christ's living presence is the answer. No amount of wielding intellectual constructs or thought-entities will truly address your question.

Post a Comment