|

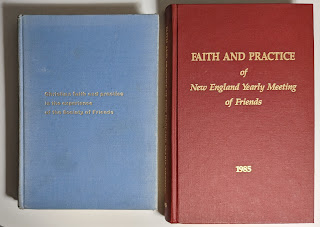

| My first two books of Quaker discipline: London (and Canadian) Yearly Meeting, 1960, and New England Yearly Meeting, 1985. |

Discipline. Until the twentieth century, the common label for the body of rules and customs by which Friends govern their meetings and lives. See also Faith and Practice.

...

Faith and Practice. A compilation of the business practices, doctrinal statements, and advices of a yearly meeting; usually includes quotations deemed appropriate from Friends over the centuries. See also Discipline.

— Thomas D. Hamm, The Quakers in America (glossary).

...

At Britain Yearly Meeting in 2018, the minute that recorded the decision to begin a full revision of Quaker Faith and Practice requested that the committee should be prayerful, joyful, creative, and bold.

— Rosie Carnall, co-clerk of Britain Yearly Meeting's Book of Discipline Revision Committee, at the opening session of Britain Yearly Meeting 2023. (Video.)

...

It was the fall of 1986, and I was a 17-year-old college freshman in an unfamiliar city far from home. My most beloved possession was my brand-new rather-plain maroon hardcover Faith and Practice of New England Yearly Meeting, hot off the presses that year. I turned to its pages nearly every day. I underlined passages I found in the book, went back, double underlined, went back, put asterisks in the margins, went back, dogeared the pages, kept coming back and finding more and more richness and relevance for my burgeoning spiritual life.

— Eden Grace, "Living Faith and Practice: Teacher and Mentor"

Among those associations of Quaker churches and meetings that we call "yearly meetings," several are in the process of revising their books of discipline. Among those quoted above, Rosie Carnall serves on a committee working on a proposed new book of discipline for her yearly meeting, and Eden Grace (whose death a few days ago I'm still struggling to deal with) served on a similar committee still at work on New England Yearly Meeting's revision.

For the last couple of years, I've been on a committee that has a similar task, but not exactly the same: our yearly meeting is new, so our book cannot exactly be a revision.

Have you been part of such a process, either as a co-laborer in drafting a discipline, or as a community member evaluating such a draft? I'd love to know how you feel about what seems to me to be a balancing act that this work must bear in mind—expressing the community's faith identity without drawing boundaries that might either alienate those already in the community or compromise our welcome to potential newcomers.

In earlier generations of Friends, books of faith and practice were not shy about proclaiming theological norms. In more liberal yearly meetings, much of the Christian content of the first two centuries of our movement was preserved in the form of extracts from cherished writings of those years, but these books also emphasized our lack of doctrinal tests and our openness to diverse voices. On the other hand, the books of discipline of more "orthodox" and evangelical Quaker bodies continued to emphasize the Christian identity of Friends. Some of those books include the Richmond Declaration of Faith, which is an artful balance of the "orthodox" and "liberal" voices of its time (1887). You can find this declaration, for example, on the "Friends Faith" page of Northwest Yearly Meeting's Web site, and in the first part of the book of discipline of Iowa Yearly Meeting (FUM), pages 1-6 to 1-18.

Twelve years ago, I wrote about some of these tendencies in this blog post.

During my years with Friends World Committee for Consultation, I observed a couple of different yearly meetings as they tried to put together new books of Christian discipline. Their Faith and Practice revision committees, in the process of submitting drafts to the larger community, kept running into an interesting phenomenon: any "advice" that made someone in the body uncomfortable was likely to be vetoed. These new books of discipline were in constant danger of becoming books of history and Quaker platitudes rather than genuine calls to a higher standard of discipleship. But truth compels me to ask an awkward question about the Faith and Practice books of previous generations: were their readers better able to submit to the authority of the group, or were some of them simply able to tolerate a larger gap between the written principles and their private behavior?

So ... did these more explicit faith descriptions actually mean that "orthodox Friends" were more likely to be model Quakers? The Richmond Declaration of Faith includes an uncompromising description of the peace testimony, but a large proportion of young male Friends whose books of discipline included that description nevertheless entered the armed forces.

Our own yearly meeting has many Friends who have strong Christian commitment and experience, and this is reflected in our willingness to identify as "Christ-centered." We also have Friends who will not tolerate being told exactly how to express their faith. As a yearly meeting, we have already minuted "What this book [of discipline] is not: A creed—a list of statements of what must be believed." As we consider the balance between "prescription" and "description," we're going to favor the second approach, which means that our committee must prioritize listening to the community.

Does this mean that anything that makes anyone uncomfortable will automatically be excluded? Not necessarily. As a committee, we are reporting to our upcoming annual sessions that a primary theme of our work is building trust. It's not just the committee listening; it is the whole community trusting each other enough to listen deeply and undefensively, hear each other's hearts and experiences, and build a Faith and Practice step by trustworthy step.

If New England Friends, with their three and a half centuries of experience, have been at their own current drafting process for over two decades, we can certainly take the time we need to listen with equal care.

I'm serious about hearing from you. Have you had experiences writing or approving a draft book of discipline? Do you have thoughts about the "prescription/description" balance? Feel free to comment in this post's "comment" field, or on Facebook or Twitter.

PS: My thoughts about our Faith and Practice work are very tentative and are mine alone. I don't speak for our committee.

(Related: Becoming the church we dreamed of, part one. Social justice IS evangelism.)

|

| Source. |

Remembering: why Margaret Fraser visits burial grounds.

My own thoughts on our experiences of Britain Yearly Meeting 2023 are complex, but here's a direct message to the world Quaker family from the sessions.

And, starting on June 6, here's a way of getting to know more of that world Quaker family, Quaker Voices from Around the World. Register here for online access.

Thinking about Eden as I listen to this song.

2 comments:

I was on one of the iterations of committees as Baltimore YM was trying to craft a Faith and Practice after the two YMs consolidated. There was an interim F&P (so named by the Supervisory Committee which by no stretch of the imagination had the authority to do that, which was an additional problem) that took the tack of emphasizing the diversity of views and understandings among Friends. It left the impression that Friends stood for nothing, and the YM easily concluded that it would not do (which is when the committee I was on was established). This failed attempt helped Friends realize that the book needed to identify certain norms of faith and practice, while not setting them down as rigid rules to which obeisance would be required.

Without that failure imposed by a group without proper authority, we might have struggled for way too long before agreeing to anything. That experience made Friends with views on certain things which were not the norm more willing to accept the different direction the committee on which I served took. There was clearly a widespread concern not to be disputatious and insist on one's own particular view - a sense that we needed to be really open to acceptance of a fair representation of general Quaker understanding. There was also an effort to be really practical with various appendices (which were largely not prescriptive) giving examples of how to do things to help Monthly Meetings.

Thank you, Bill. I wasn't aware of any of this at the time.

Post a Comment