|

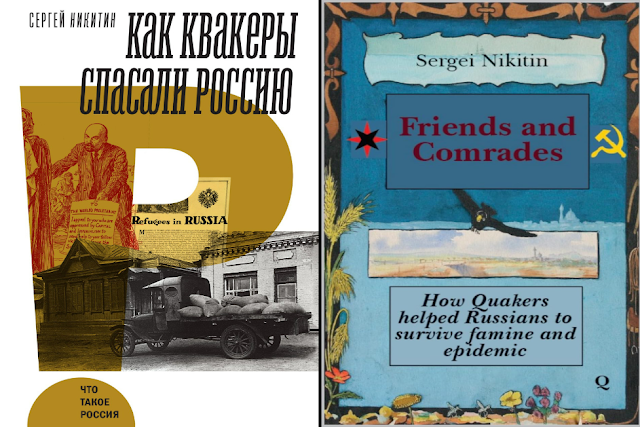

| Sergei Nikitin's book on the history of Friends relief missions in Russia, particularly in the years 1916-1931, and its English translation, Friends and Comrades. Translation by Suzanne Eade Roberts. Link to purchase the print version. Link to purchase the Kindle version. |

In 1947, the Nobel Committee of Norway's parliament awarded that year's Nobel Peace Prize to the Quakers, "...represented by their two great relief organizations, the Friends Service Council in London and the American Friends Service Committee in Philadelphia."

In his presentation speech at the award ceremony, Gunnar Jahn cited Quakers' role in peace and relief work in many countries, including Russia: "It is through silent assistance from the nameless to the nameless that they have worked to promote the fraternity between nations cited in the will of Alfred Nobel." (My emphasis.)

At the peak of the famine relief work, over 400,000 Russians were depending on Quaker food rations to stay alive. 20,000 to 30,000 people a month were treated in their malaria clinics in Buzuluk. In the history of this campaign, many people involved will indeed remain "nameless." We will not know most of the people whose lives were saved from starvation and disease through Quakers' efforts, and most of those who provided prayer and money to this work will also remain unknown. Thanks to Sergei Nikitin's book Friends and Comrades, however, the full scale of this effort, and the names of many of its central figures, are made known and brought to life.

Sergei's book is organized into five broad areas, four of which correspond to the chronology of British and USA Friends' relief and reconstruction work in Russia:

- Assistance to World War I refugees, 1916-1918.

- Assistance to children who were suffering as a result of the post-revolutionary civil war in Russia, 1920-21.

- The massive famine relief, medical aid, and agricultural rehabilitation efforts of 1921-27, centered in the towns of Buzuluk and Sorochinsk, and the ongoing official Quaker presence in the USSR that ended in 1931.

- Individual Quakers' continuing involvements in the Soviet Union after 1931.

- Finally, reflections on the complex relationships between Friends and the Soviet authorities throughout this history.

Missions of this magnitude generate an enormous amount of archival material—logistical records and ledgers; official and unofficial correspondence among every conceivable subset of actors; public relations and fundraising materials; news accounts; photos, films, and graphics of all kinds; and memoirs. It is a huge challenge to make a judicious selection that can bring these voices into our own time with an appropriate mix of accurate reportage and fair analysis, all in a package of manageable length. It's my judgment that Sergei has succeeded.

Previous treatments of this story include an article by John Forbes in the Bulletin of Friends Historical Association, "American Friends and Russian Relief 1917-1927," published in two parts (Spring and Autumn 1952). Richenda C. Scott's Quakers in Russia (1964) ranges from the first Quaker contacts with Peter the Great all the way to her own time, but more than half of her excellent book is devoted to this same famine and refugee relief work. More recently, David McFadden and Claire Gorfinkel told this story in a more thematic approach, in their book Constructive Spirit: Quakers in Revolutionary Russia (2004), to which Sergei Nikitin contributed an introductory chapter in the form of a personal overview.

|

| One of Sergei Nikitin's first articles on the famine relief mission, Jan.-Feb. 1998. |

Sergei took full advantage of the archives already available to previous authors, although he often made different selections from the material. All of these historians described a crucial debate among the Quakers: was their work of famine relief and medical aid in itself the main Quaker message to Russians, or was it a means by which Friends could spread their spiritual beliefs in Russia, and also build relationships with Tolstoyans and likeminded Russians? Sergei and others quote a proposed memorandum to the Bolshevik authorities that was composed by those supporting the latter priority:

[Sergei quotes the memorandum:] ‘We are upon an active campaign to overcome the barriers of race and class and thus to make of all humanity a “Society of Friends”’. The letter’s authors were frank about the historical examples of Quakers’ dissidence due to their basic principles: ‘This has led us to follow a course, on some occasions, different from that of fellow citizens; even to act contrary to the law of our country when our legislators bid us violate our principles, particularly when called upon to take human life in warfare’. In closing, the Quakers asked the Bolsheviks openly: ‘Hence we seek to know your attitude towards us, and our concern to unite in fellowship with Russian people. With that in view we desire to ask if you will allow representatives of the Society of Friends to come to Russia for the purpose of establishing independent work for the administration of physical relief and to give expression to our international and spiritual ideals and principles of life’.

Arthur Watts, a British Quaker based in Moscow, was viscerally opposed to this approach, believing that any stated purpose other than strictly disinterested relief work would threaten their hitherto relatively unfettered access. Nikitin takes up the story:

He [Watts] called the draft ‘A mild lecture and an explanation of our “chief concerns”’. Reasonably enough, he criticised the part of the text where the Quakers talked about social class: ‘It will be difficult for me to convince the recipients of the Activeness of your “campaign to overcome the barriers […] of class”’. On this point, Watts was right to reproach the authors of the letter of hypocrisy, reminding them that British Quakers still withheld control in industry from their workers, and that their British employees did not have control of anything. He wrote: ‘I have a strong objection to pretending to be better than we are’.

Arthur Watts also condemned the London committee’s apparent caution and concern that Quaker help would be interpreted as an expression of sympathy for Bolshevik methods. He wrote that he could not believe that Quakers might abstain from helping Russian children out of fear of being misunderstood. He added: ‘This is really most unworthy of you. Did you demand a statement from the Tsarist Government that our help was not to be taken as indicating approval of their aims and methods?’ He drew parallels with the parables in the Bible, asking, ‘I wonder if Christ thought of issuing a Statement of Aims before raising the Centurion’s daughter’, and made the sarcastic comment that if the Good Samaritan had drawn up a careful minute, ‘we might have admired his “Quaker Caution” but it would have spoilt the point of the parable’.

Only Sergei Nikitin includes Watts's commentary on class hypocrisy.

One of the new elements that Sergei brings to his book is his research in Russian government archives. Previous histories looked at these events primarily through the eyes of the British and American participants. For example, Sergei touches on the debates between the American Friends Service Committee leadership, and the future Quaker president of the USA, Herbert Hoover, who headed the American Relief Administration and its program of famine relief. McFadden and Gorfinkel's Constructive Spirit goes into these conflicts in fascinating detail, illustrated by numerous extracts from letters and memoirs. Sergei gives briefer treatment to this aspect of the history, although he describes the awkward consequences of this conflict for the relationships between the British and American relief teams.

Thanks to his Russian sources, we learn far more about the Bolshevik authorities' own secret reports from the hardest-hit famine districts, their scrutiny of the Quaker teams, their generally favorable assessments of those teams, their worries about Quaker influences on the population, and the role of the secret police in infiltrating and monitoring the Quaker work. Nikitin also describes the sad fate, during the Stalinist terror, of some of those Russians who collaborated in the work—and, ironically enough, some of those who spied on the Quakers and were shot anyway.

Equally powerful in their own way are the numerous statistical reports provided by Russian sources. According to archives held in Buzuluk, "... in June 1922, American and British Quakers fed 85% of the population in need in Buzuluk district!"

Sergei's own voice and viewpoint are the other distinctive element of his book. He observes and comments as a Russian. He came to this whole history with something of the same astonishment that I myself heard from people in Buzuluk as they remembered their great-grandparents's recollections, saying in effect, "How could it be that these British and American people cared enough about us to make the hazardous journey, face all the risks of civil war and famine, and even die for us?" (Typhus killed two of the women on the teams, Mary Pattison and Violet Tillard.) Sergei reports on some of the dozens of interviews he conducted among people with first-hand experiences of the famine years, and among their descendants.

Sergei does not just focus on the heroism, but also covers the mistakes, disorganization, and discouragements that inevitably accompany disaster relief in unfamiliar surroundings, where absolutely nobody arrives with adequate preparation, and everyone involved is learning as they go. Furthermore, Quaker idealism (in some cases, taking the form of sympathy for the Bolshevik cause) could have made them "useful idiots" for the new regime. Some Quakers assumed that their Russian counterparts would be as honest as they themselves were. Sergei gives several examples of the Quaker capacity to believe what they wanted to believe despite evidence to the contrary. Nevertheless, his overall assessment is generous:

Looking back today at the history of interaction between Quakers and the Russian authorities, the Society of Friends clearly did extraordinary work. Through incredible effort, hundreds of thousands of people were saved from death. Goodness, honesty, openness and a willingness to help–these characteristics of the British and American Quakers left a warm glow in the heart of each Russian who interacted with them.

Among the book's useful material is a detailed chronology of these years, as well as a roster of every team member involved in the 1916-1919 mission and in the 1920-31 mission. The author includes many archival photos and provides bibliographies of his English-language and Russian-language sources.

Thanksgiving update: information on the documentary film Famine, which is a valuable supplement to Sergei's book, and which includes an interview with him.

Michael G. Azar, Public Orthodoxy, on Orthodox Christians in Gaza City.

Steve Hoffman on being people of mercy.

British Quakers brief parliamentarians on climate justice.

Safeguarding vulnerable people in church: Juulie Downs on the importance of clear policy and record-keeping.

60 Minutes on Clarksdale's blues heritage, and an interview with Christone "Kingfish" Ingram.

[Deleted from YouTube; now available for streaming on Paramount+.]

No comments:

Post a Comment